Australian major airports 2023-4: revenues were stratospheric, as light handed regime persists

For more than two decades a 'light touch' regulatory regime has existed in Australia (and New Zealand), which to all intents and purposes, allows airports to charge whatever they like to airlines that use their facilities.

It is so light it might blow away in a gust of wind, and it has enabled airports to make EBITDA margins (a measure of profitability) well above the average for other parts of the world, and even greater than found in the hi-tech sector globally.

While margins reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, they were still very high even for normal times elsewhere.

The argument against this degree of profitability that is put forward by the airlines is that it is often not matched by the degree of investment into airport infrastructure that they require, although that is debatable.

With the pandemic coming to an end, this disagreement - which had gone on the back burner during its period of impact - is bound to raise its ugly head again.

Figures released by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission will again put pressure on airports, either to reduce charges or to offer more bang for the airlines' buck.

Meanwhile, the position in New Zealand could become even more acute, with IATA demanding urgent changes to the country's Economic Regulatory Framework for Airports.

Summary

- Major Australian airports achieved unprecedented aeronautical revenues, with the four monitored facilities there racking up their highest ever levels in 2023-24.

- Sydney’s airport was the most profitable of the lot; Perth the only one to report a fall in profits.

- Profits arose from both aeronautical and non-aero sources.

- ‘Good’ ratings for service levels, but not from the airlines.

- The light handed aviation regulatory regime in Australia continues to rule...and dates back over two decades.

- But does the investment match the generous terms on revenues?

- The system ensured that the airports stayed profitable throughout the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- These airports even outperform the hi-tech sectors.

- Sydney’s airport’s earnings multiple almost doubled between 2003 and 2022.

- EBITDA margins for the four monitored airports varied from 45% to 77% in 2020/21, with an average of 62.1%.

- Major infrastructure projects are holistic in nature, with no preference to any one model, and with USD10 billion coming in capital expenditure on modernisation.

- More transparency and scrutiny is needed in both Australia and New Zealand says IATA.

- A harder line still is being taken in New Zealand, where IATA has called for urgent changes to the regulatory framework.

Major Australian airports achieved unprecedented aeronautical revenues, with the four monitored facilities racking up their highest ever levels

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) reports that in 2023-24, major Australian airports achieved unprecedented aeronautical revenues, with a notable 24.3% increase to AUD2.6 billion (USD1.64 billion), despite handling fewer passengers than the pre-pandemic levels.

The ACCC highlighted the importance of ongoing investment to address demand and improve capacity at major airports. For example, the construction plan for a third runway at Melbourne's Tullamarine Airport has been approved, with completion expected in 2031 to accommodate growing demand and to enhance capacity.

According to the CAPA - Centre for Aviation Airport Construction Database that project will cost AUD3 billion, and is being funded entirely by the airport, with no government financing in the construction.

The ACCC noted the four major monitored facilities (alphabetically) Brisbane Airport, Melbourne Tullamarine Airport, Perth Airport and Sydney Kingsford Smith Airport, recorded their "highest ever aeronautical revenues" in 2023-24.

The table below shows passenger figures in 2019, 2023 and 2024.

|

Airport |

Passenger traffic 2024 (million) |

Versus 2023 (%) |

Versus 2019 (%) |

|

23.3 |

+9.7 |

(-2.9) |

|

|

35.5 |

+6.9 |

(-4.3) |

|

|

16.9 |

+10.4 |

+14.2 |

|

|

Sydney Kingsford Smith |

41.5 |

+7.1 |

(-6.5) |

|

Average |

29.3 |

+8.5 |

+0.1 |

Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation Airport Profiles.

Perth was the only one of the four to report an increase over 2019, but conversely was the only one to note a fall in aeronautical profits, albeit for reasons peculiar to it (see later).

All four airports are expected to record passenger numbers greater than in 2019 by the end of 2025.

Sydney Kingsford Smith will face competition from the AUD5.3 billion Western Sydney International (Nancy-Bird Walton) Airport from 2026, so this is the last year in which it will have unchallenged access to Sydney region commercial passengers.

Sydney's airport was the most profitable of the lot; Perth the only one to report a fall in profits

Sydney Kingsford Smith Airport was the most profitable of the four major airports, recording an aeronautical operating profit of AUD570.5 million (USD360.88 million), which represented a 20.2% return on its aeronautical assets.

Brisbane Airport and Melbourne Tullamarine Airport recorded aeronautical operating profits of AUD194.7 million (USD123.16 million) and AUD198.9 million (USD125.82 million) respectively, despite Brisbane Airport catering to "far fewer" passengers (12.2 million fewer) than Melbourne Airport;

Perth Airport was the only monitored airport to report a fall in aeronautical profits: down by 29.1%, to AUD70.7 million (USD44.72 million), after a "significant increase" in security and depreciation expenses.

Profits arising from both aeronautical and non-aero sources

Looking at more detail into the financial results and the performance levels that dictated them, operating profits from car parking grew for all four airports during the period. All recorded operating profit margins above 60% for the second consecutive year for their car parking operations.

Revenues from landside transport access services, such as rideshare operators, taxis and buses, grew by 18%, to AUD69.6 million (USD44.02 million), as vehicle numbers rebounded.

'Good' ratings for service levels, but not from the airlines

All four airports maintained an average overall rating of 'good' for the quality of service and facilities in 2023-24.

Ratings by airlines generally fell, and all four airports received only a 'satisfactory' result. The most common airline concerns related to aircraft parking facilities, baggage facilities, common user check-in facilities, aerobridges, and public amenities.

The increase in aeronautical revenues in the period was driven in large part by the continued recovery in international passenger numbers, which rose by 32.1% at the four monitored airports.

That last increase is the key to the profitability of Australian airports.

The light handed aviation regulatory regime in Australia continues to rule...

Those airports in Australia, and in New Zealand too, benefit from the lightest-handed regulatory regimes to be found anywhere in the world, with government intervention eschewed in favour of 'natural' regulation brought about by market forces and airport/airline negotiations.

The ACCC tends to restrict itself merely to monitoring aeronautical prices, and the quality of service at the major airports - meaning revenues, costs, and profits, and the quality of aeronautical, car parking, and landside access services at the Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, and Brisbane airports.

Apart from some regional services at Sydney Airport, governments do not intervene in the setting of charges or other terms of access.

…and dates back over two decades

This light-handed approach by the government to price regulation of airport services, with market power dates back to 2002, was in recognition of what was perceived to be effective competition and strong buying power from the airlines. Moreover, the majority of the principal airports had been privatised in the late 1990s (Sydney followed later, in 2003), to be operated under long-term leases.

So there was every incentive for both the parties, airports and airlines, to agree common boundaries between themselves, rather than rely on a government mechanism for approval that might be hidebound by dogma, inertia and red tape.

Airport users, including airlines and operators of landside services, negotiate directly with airport operators on charges and other terms of access to infrastructure services.

The leases on these airports also include conditions, such as the requirement to supply services to air transport operators, invest in airport infrastructure, and to obtain ministerial approval for major developments.

The light-handed approach is intended to facilitate commercially negotiated outcomes, and is seen as promoting investment and efficiency.

But does the investment match the generous terms on revenues?

Although, internationally, airport operators may gasp at the profitability of the Australian airports, if there has been a bone of contention locally it has been, as might be expected, the level of charges and that degree of profitability, versus the degree of investment in infrastructure.

CAPA - Centre for Aviation has investigated the Australian charging regime on numerous occasions, in the first instance as long ago as 2007, when the origination of the system was examined and the question - still a pertinent one - was asked: is it a light-handed one, or would 'limp wristed' be more accurate? ('Limp-wristed', meaning ineffectual, was a common business phrase at the time; not so much these days).

See original CAPA - Centre for Aviation report from Jul-2007: Airport pricing - light handed or limp wristed? The Australian experience (N.B. This report, originally part of the then Airport Investor Monthly publication, is archived, and uses some data sources that are no longer available).

The second one, Australian airport pricing. Productivity Commission review to be brought forward, followed in Dec-2010, in anticipation of a Productivity Commission review of airport pricing, investment and services as part of a public inquiry into the economic regulation of major Australian airports that was announced earlier in that year.

Despite numerous reviews since then, and immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic, the competition regulator (ACCC) remaining worried that limited regulation of the nation's four big monopoly airports results in big profits that push up airfares; the approach remains much the same in 2025.

The COVID-19 pandemic diverted attention from the issue, but as 2023-24 airport financial results become known, it will undoubtedly make a return.

The system ensured the airports stayed profitable throughout the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic

So far, detailed statements are few in number, but just a glance at those from the two main pandemic financial years, 2020 and 2021 alone, reveals how the airports were able to remain profitable with hugely reduced traffic.

CAPA - Centre for Aviation has previously noted that Australian airport EBITDA margins (the ratio of EBITDA [Earnings before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation - a method of assessing a company's core business performance] to total revenue) have been as high as 86%.

Compare that to an industry pre-pandemic average of 45%.

That is much the same as saying "we are making 86% profit on normal operations".

These airports even outperform the hi-tech sectors

And although the airport industry as a whole compares reasonably well to, say, the hi-tech and social technology ones by this measure, these 'limp-wristedly' regulated airports, with margins of 75%-85% nearly always outscore it.

The table below is of the EBITDA margins for five corporations in the hi-tech and social-tech ones.

EBITDA margins for five major corporations, hi-tech and social

|

Organisation |

Declared EBITDA margin |

Date |

|

18.9% |

Mar-2025 |

|

|

META (Facebook) |

51.6% |

Dec-2024 |

|

Microsoft |

52.8% |

Mar-2035 |

|

Alphabet (Google) |

36.5% |

Dec-2024 |

|

Nvidia (AI microchips) |

63.8% |

Jan-2023 |

Source: author research.

Little wonder then that major Australian airports attract widespread interest, when their owners choose to divest some or all of their equity (as has happened recently), assuming that buyers can afford them.

Sydney's airport's earnings multiple almost doubled between 2003 and 2022

For example, in the 2021/22 takeover of Sydney Airport by a consortium of (mainly) Australian investment and pension funds, and the US one (GIP), the enterprise value (EV) was approximately AUD32 billion, and the acquisition price represented a multiple of approximately 24.2 times the 2019 EBITDA.

The earnings multiple on the first sale, in 2003, just after the light-handed system came into effect, had been just 14.4 times.

EBITDA margins for the four airports varied from 45% to 77% in 2020/21, with an average of 62.1%

It is only necessary to look at the financial reports for these four airports for the two main pandemic years, 2020 and 2021, to understand how they benefitted from this lack of formal government control, while acknowledging that other factors, such as the availability of intra-state air services (some had them, others did not) and strict house management would have played a part.

Major Australian airports: EBITDA margin 2020 and 2021

|

Airport, |

EBITDA Margin 2020 |

EBITDA Margin 2021 |

|

75% |

55% |

|

|

61% |

n/a |

|

|

61.3% |

60.4% |

|

|

45% |

77.2% |

Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation Airport Profiles and author research.

Those statistics would have been warmly, even ecstatically, received by airport management in many parts of the world in 'normal' times, let alone during the worldwide pandemic.

But what about the other side of the coin? How does infrastructure facility investment compare to these very high charges to airlines?

Major projects are holistic in nature, with no preference to any one model, and with USD10 billion coming in capital expenditure on modernisation

It is fair to say that the concept of the low cost airport or terminal never really caught on in Australia, as it did in the UK, Europe and Asia at the start of this century, even though today 24% of all seats within and to/from Australia are on low cost airlines.

Thus, construction projects tend to be holistic, embracing all business models. Such as at Perth, where its AUD5 billion 'One Airport' project only segregates by airline, not business model; so there will be a new Qantas terminal.

Meanwhile, Brisbane Airport will revamp its international terminal as part of its AUD5 billion 'Future BNE' terminal.

The four major airports held back on investment during the pandemic period, but this is starting to change, now that there is more certainty around demand for travel.

There are significant capital works at three of the four airports at least - Brisbane and Perth as above, as well as at Melbourne, as mentioned earlier - which should help increase capacity.

Between the three of them there is some USD10 billion coming in capital expenditure on modernisation.

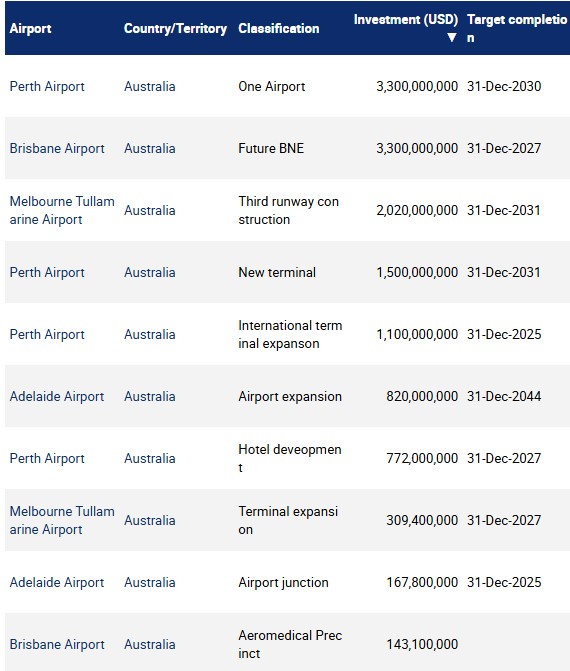

Construction projects at major Australian Airports

Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation Airport Construction Database.

In 2023-4 the airports invested AUD985.1 million (USD623.15 million) in aeronautical facilities, a figure that is set to increase in the coming years.

Melbourne Airport's AUD502.3 million (USD317.74 million) investment accounted for more than half of the total investment in aeronautical assets in that period.

More transparency and scrutiny is needed

So, arguably, the construction is taking place.

Whether it matches the high earnings from airlines is a moot point, and one not likely to be agreed any time soon, by ACCC or anyone else.

Indeed, the trade body Airlines for Australia and New Zealand (A4ANZ) stated in response to the ACCC monitoring report that airports in Australia and New Zealand together are targeting investments of around AUD30 billion (USD19 billion) over the next decade, which is "around twice as much" as during the 10 years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic.

But further "transparency and scrutiny" are required to ensure that capital expenditure is "efficient and directed to serving the interests of airlines and their customers".

Although airlines welcome investment, it "must be efficient and timely[,] and most importantly serve the needs of airlines and their customers, not just enhance the profits of airports."

A harder line still is being taken in New Zealand, where IATA has called for urgent changes to the regulatory framework

In New Zealand, the Commerce Commission has published its final report on Auckland International Airport's Price Setting Event 4 (PSE4), which covers the period for FY2023 to FY2027. Auckland is the country's principal aviation gateway.

The report concluded that the airport's forecast revenue is excessive, and its targeted returns are unreasonably high, with its forecast investment falling "within a reasonable range".

The excess profit of NZD190 million (USD107.8 million) represents a targeted return of 8.73% from priced aeronautical activities, compared to the Commission's estimated reasonable return of between 7.3% and 7.8%. The airport has announced plans to discount its prices for airline passenger charges in response to the report.

As a direct consequence, IATA called for "urgent changes" to New Zealand's Economic Regulatory Framework for Airports, stating that it is not surprising that the Commerce Commission has concluded that Auckland Airport's charges are excessive. And that while the airport has responded by lowering its charges over the next two years in response to the review, the process does highlight that the economic regulatory framework in its current form is not fit for purpose, and change is urgently needed.

IATA highlighted the following concerns:

- The 'light touch' regulatory approach means that Auckland Airport can set the aeronautical pricing as it wishes. IATA stated that Auckland Airport is "the sole monopoly provider" and can "game the regulatory process by setting their pricing artificially high at the start of the regulatory process, and then respond, if they so wish, by lowering their pricing following the conclusion by the regulator or by ignoring the report";

- Non-aeronautical activities are excluded from the purview of the Commerce Commission (i.e. the dual till mechanism is in play, and profits from concession services are not used to cover infrastructure cost at all - a regular feature elsewhere);

- Auckland Airport is investing significantly in infrastructure, but there are outstanding concerns highlighted by airlines about the size, phasing, cost allocation, and affordability of the investments. IATA believes that some of these costs could have been avoided if infrastructure planning and investments had been managed appropriately in the past.

IATA concluded by saying, "The current consultation process with Auckland Airport is ineffective[,] and may not deliver outcomes that are in the best interests of passengers".

The phony war that took over during the pandemic is over, and it is most likely to be the case that high charges versus investment will soon return to be the topic that dominates airline-airport relationships in both Australia and New Zealand.

Further reading from Mar-2024 concerned with claims that Australia's regional airports could not survive without enhanced federal budget assistance: Australia's regional airports 'unviable' without Federal budget aid; three examples - part one; part two.